Anna Blessmann selected exhibitions and projects

The title of the show Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain is a mnemonic used to recall the key colours of the spectrum ( red, orange, yellow, green, blue indigo, violet)

With over 13,500 works of art spanning five centuries, the Government Art Collection is the most dispersed collection of British art in the world. Placed in offices and official residences, two thirds of the works are on display in British government buildings in nearly every capital city. Dating from 1898, the collection helps promote British art and history while contributing to cultural diplomacy.

Photos: Tony Harris

With over 13,500 works of art spanning five centuries, the Government Art Collection is the most dispersed collection of British art in the world. Placed in offices and official residences, two thirds of the works are on display in British government buildings in nearly every capital city. Dating from 1898, the collection helps promote British art and history while contributing to cultural diplomacy.

Photos: Tony Harris

David Adamo, Laura Aldridge, Hany Armanious, Aaron Angell, Ei Arakawa & Henning Bohl, Anna Blessman & Peter Saville, Wolfgang Breuer & Lucie Stahl, Pavel Buechler, Steven Claydon, Keith Coventry, Matthew Darbyshire, Nicolas Deshayes, Jeason Dodge, Paul Elliman, Ruth Ewan, Alex Frost, Ryan Gander, Martino Gamper, Brian Griffiths, Richard Healy, Roger Hiorns, Andy Holden, Richard Hughes, Tom Humphreys, Phillip Lai, Jim Lambie, Jack Lavender, Hannah Lees, Sherrie Levine, Helen Marten, Simon Martin, Mike Nelson, Chrisodoulos Panayiotou, Magali Reus, David Shrigley, Ricky Swallow, Mungo Thomson, Hayley Tompkins, Francis Uprichard, Franz West, Bedwyr Williams

This survey of contemporary sculpture in microcosm takes inspiration from the collection of the 19th century anthropological archaeologist Lieutenant General Augustus Henry Pitt-Rivers (1827–1900). However, it refuses his belief in social Darwinism and celebrates something of the reverse, its title being a corruption of his lecture ‘On the Evolution of Culture’ (delivered to the Royal Institution of Great Britain in 1975).

Works are presented to echo Pitt Rivers’ domestic display of ethnographic objects and archaeological find arrayed over a snooker table. The exhibition therefore also acknowledges Man Ray’s painting ‘La Fortune’ (1938 ) and Sherrie Levine’s sculptural approximation of it (1990).

The exhibition rejects the crafted neo-classicism promoted by 19th century industrialists and landowners such as Pitt-Rivers. It also opposes later, early twentieth century works of applied art included in exhibition such as ‘Modern Art for the Table’ (1934). Instead it celebrates dysfunction, redundancy and crude fetish.

Thanks are due to Roy Stephenson and Caroline McDonald for their invaluable assistance in sourcing archaeological specimens for the exhibition.

This survey of contemporary sculpture in microcosm takes inspiration from the collection of the 19th century anthropological archaeologist Lieutenant General Augustus Henry Pitt-Rivers (1827–1900). However, it refuses his belief in social Darwinism and celebrates something of the reverse, its title being a corruption of his lecture ‘On the Evolution of Culture’ (delivered to the Royal Institution of Great Britain in 1975).

Works are presented to echo Pitt Rivers’ domestic display of ethnographic objects and archaeological find arrayed over a snooker table. The exhibition therefore also acknowledges Man Ray’s painting ‘La Fortune’ (1938 ) and Sherrie Levine’s sculptural approximation of it (1990).

The exhibition rejects the crafted neo-classicism promoted by 19th century industrialists and landowners such as Pitt-Rivers. It also opposes later, early twentieth century works of applied art included in exhibition such as ‘Modern Art for the Table’ (1934). Instead it celebrates dysfunction, redundancy and crude fetish.

Thanks are due to Roy Stephenson and Caroline McDonald for their invaluable assistance in sourcing archaeological specimens for the exhibition.

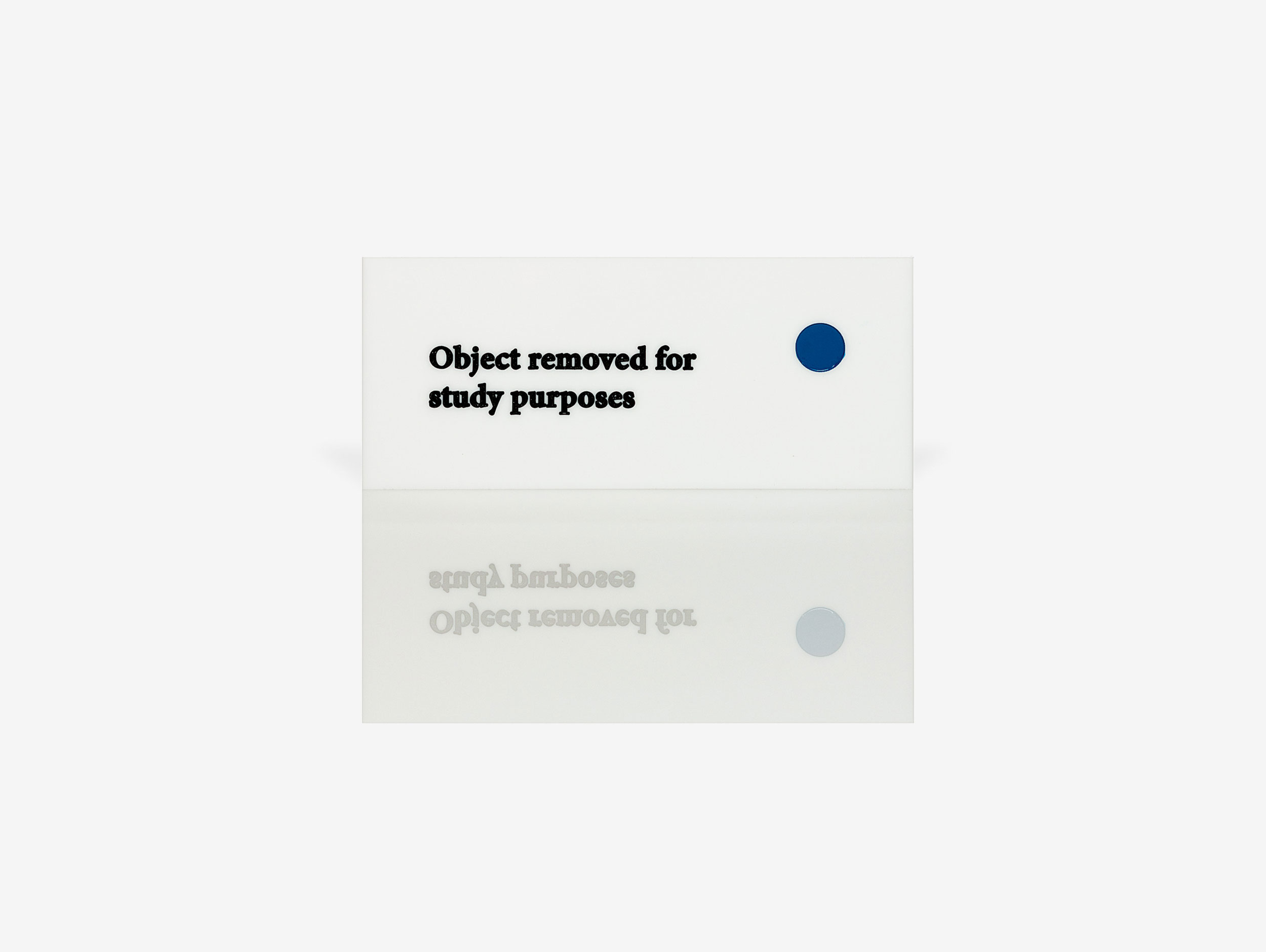

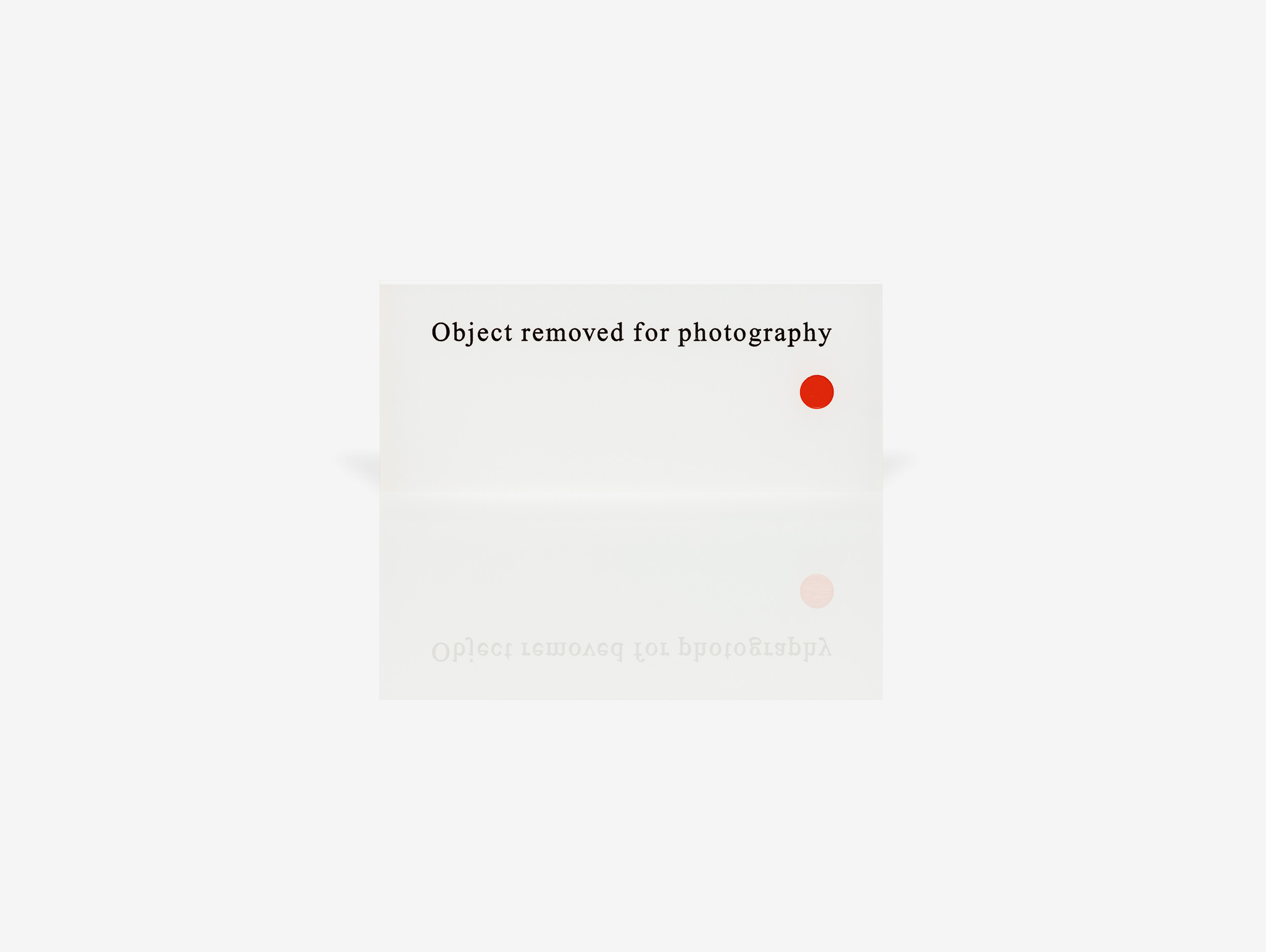

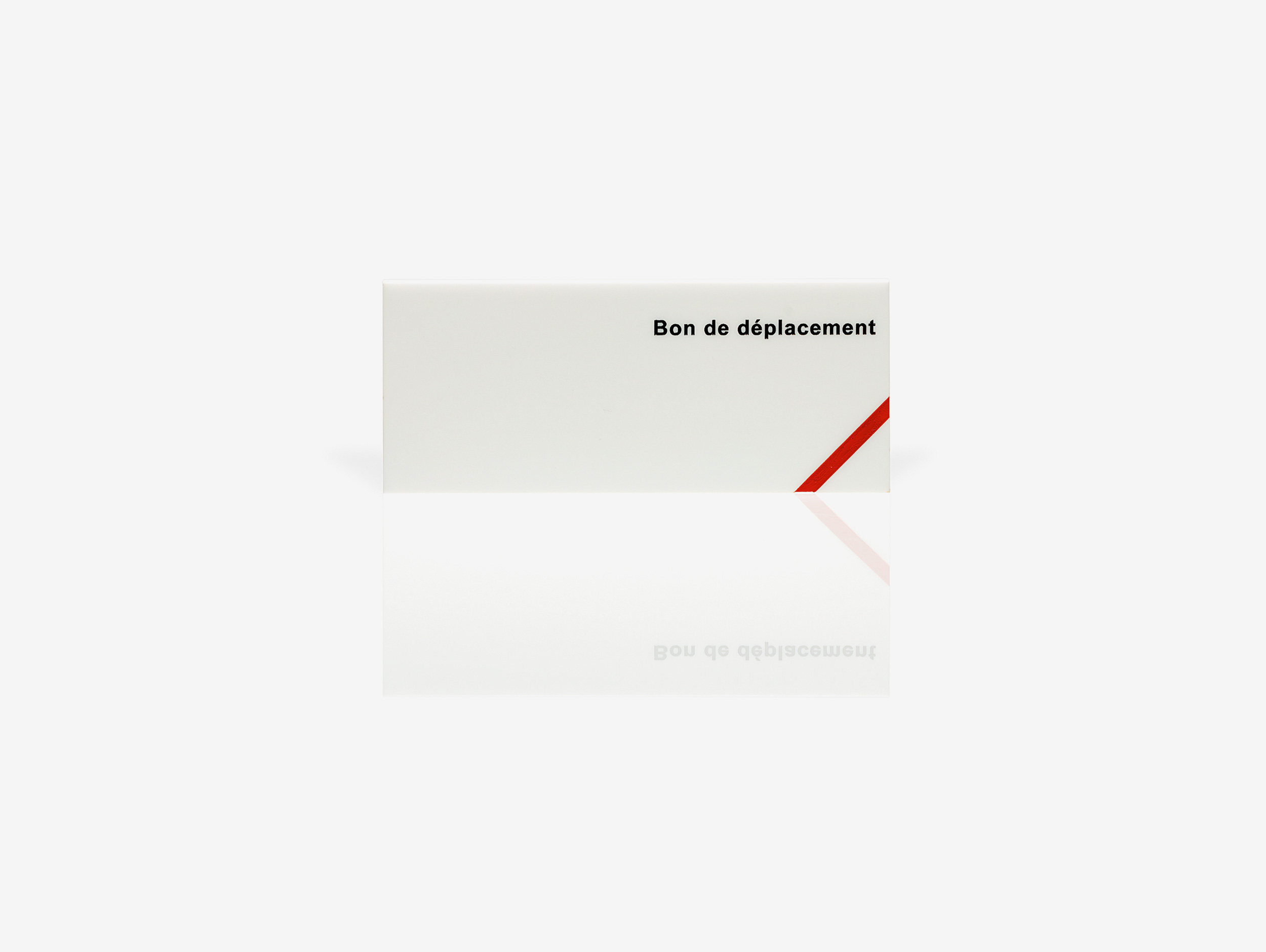

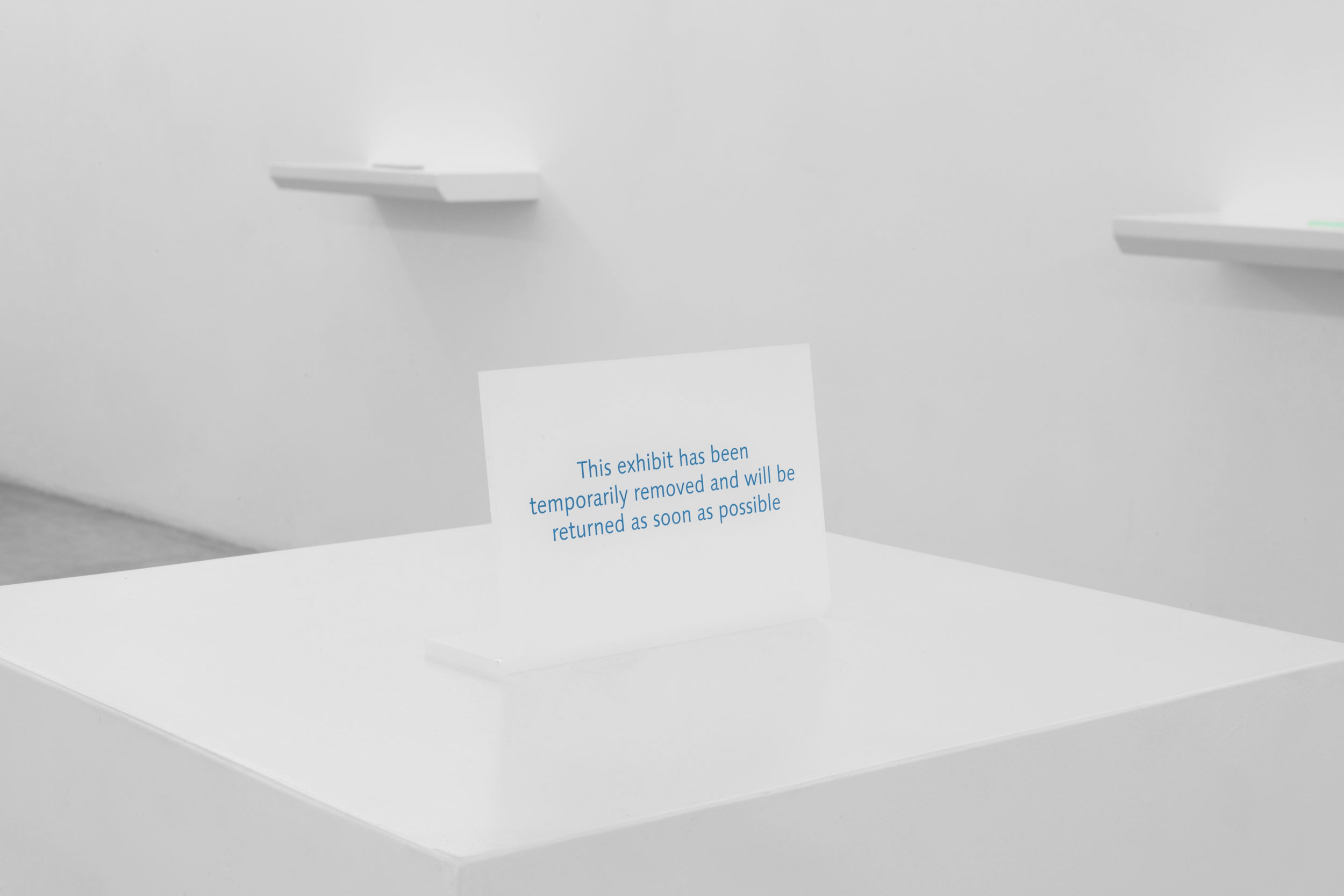

You might never have noticed them; you might have walked past ten times, twenty times, on your way through the vast collections of the V&A, or the Met, or the Louvre, and not have seen them. Small signs, sometimes glassily translucent, sometimes tagged with a brightly coloured dot, declaring ‘object removed for photography’, or otherwise for restoration, or maybe research. Temporary interruptions in the logic and flow of the museological display, they make a double promise; that an object was there and that it will be returned.

Anna Blessmann began noticing and photographing these placeholders in museums and galleries across the world more than a decade ago. The series of photographs that she produced of these discreet and tucked-away missives provides a loose taxonomy of their varying forms and tones, but their interest lies less in the differences between individual examples and more in what, as a genre, these stand-ins stand for.

They act as markers for missing objects but rather than representing a lack of something, they in fact act as guarantors of possession in absentia, assuring the integrity of the collection. (Their twin sisters are the small red stickers that you might find stuck next to sold items in a furniture shop, or maybe even at an art fair. These also symbolise possession, but through an inverse mechanism. In their case, the object is physically present but, having already been purchased, is no longer available. The dots therefore perform an absenting of sorts.) As to what form the absent objects take, this may be suggested by a halo of sun-bleached backing paper or the faint outline impressed in a fabric covering by the weight of years, but on this matter the signs themselves are silent. They divulge nothing; representing whilst remaining entirely non-representational. Which is to say that they leave endless room for imagining.

Anna Blessmann and Peter Saville use the form of these museum placeholders to explore ideas of possession and collection, potential and imagination, and the art object itself. Available for purchase as a limited edition, these ‘Art Accessories’ have a transformative potential: any domestic setting can become a collection. As artworks in their own right, they allow the public to become collectors even as they explicitly disavow their own status as object.

These works are playful and slightly irreverent, gently mocking the imperial passion for possession and categorisation from which the museum was born. But they also get to the heart of what it is to collect and the slipperiness of this term in an era when the notion of the art object is undergoing sustained critique: by the ideas proposed by relational aesthetics; by an increased blurring of the formally discrete realms of art and performance; by technological advancements which have complicated the notions of possession and authorship. Blessmann and Saville recognize the impulse to possess, to have, to collect; they play up to it. But they also recognize its limitations, declaring that it is enough to imagine and to suggest.

Amy Sherlock

Photos: Peter Abrahams

Anna Blessmann began noticing and photographing these placeholders in museums and galleries across the world more than a decade ago. The series of photographs that she produced of these discreet and tucked-away missives provides a loose taxonomy of their varying forms and tones, but their interest lies less in the differences between individual examples and more in what, as a genre, these stand-ins stand for.

They act as markers for missing objects but rather than representing a lack of something, they in fact act as guarantors of possession in absentia, assuring the integrity of the collection. (Their twin sisters are the small red stickers that you might find stuck next to sold items in a furniture shop, or maybe even at an art fair. These also symbolise possession, but through an inverse mechanism. In their case, the object is physically present but, having already been purchased, is no longer available. The dots therefore perform an absenting of sorts.) As to what form the absent objects take, this may be suggested by a halo of sun-bleached backing paper or the faint outline impressed in a fabric covering by the weight of years, but on this matter the signs themselves are silent. They divulge nothing; representing whilst remaining entirely non-representational. Which is to say that they leave endless room for imagining.

Anna Blessmann and Peter Saville use the form of these museum placeholders to explore ideas of possession and collection, potential and imagination, and the art object itself. Available for purchase as a limited edition, these ‘Art Accessories’ have a transformative potential: any domestic setting can become a collection. As artworks in their own right, they allow the public to become collectors even as they explicitly disavow their own status as object.

These works are playful and slightly irreverent, gently mocking the imperial passion for possession and categorisation from which the museum was born. But they also get to the heart of what it is to collect and the slipperiness of this term in an era when the notion of the art object is undergoing sustained critique: by the ideas proposed by relational aesthetics; by an increased blurring of the formally discrete realms of art and performance; by technological advancements which have complicated the notions of possession and authorship. Blessmann and Saville recognize the impulse to possess, to have, to collect; they play up to it. But they also recognize its limitations, declaring that it is enough to imagine and to suggest.

Amy Sherlock

Photos: Peter Abrahams

Back

Copyright Anna Blessmann